1. The game of one-upmanship

People who think the law of non-contradiction and/or the law of the excluded middle is/are expendable have simply not sufficiently observed and analyzed the formation of knowledge within themselves. They think it is just a matter of playing with words, and they are free to assert that some things might be “both A and not A” and/or “neither A nor not A”. But they do not pay attention to how that judgment arises and is itself judged.

They view “A is A”, etc.[1], as verbal statements like any other, and think they can negate such statements like all others, saying “A is not A”, etc. But in fact, negation is not possible as a rational act without acceptance of the significance of negation inherent in the second and third laws of thought, in comparison to the first law of thought. To say “not” at all meaningfully, I must first accept that “A cannot be not A” and that “there’s no third alternative to A and not A”.[2]

To try to introduce some other (less demanding) definition of negation is impossible, for true negation would still have to be thought of (in a hidden manner or using other words). Inventing a “many-valued logic” or a “fuzzy logic” cannot to do away with standard two-valued logic – the latter still remains operative, even if without words, on a subconscious level. We have no way to think conceptually without affirmation and denial; we can only pretend to do so.

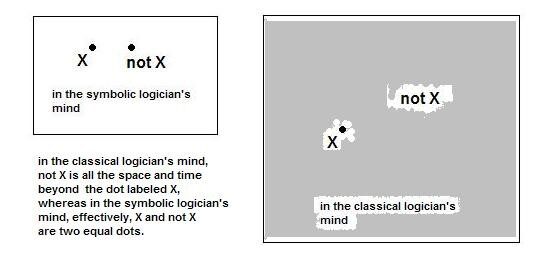

Many “modern” logicians are so imprisoned by symbolic logic that they have lost contact with the intended meanings of their symbols. For this reason, the symbols ‘X’ and ‘not X’ seem equivalent to them, like ‘X’ and ‘Y’. But for classical logicians, a term and its negation have a special relationship. The negation of X refers to all but X, i.e. everything that is or might be in the whole universe other than X.[3]

The diagram below illustrates how differently these people effectively visualize negation:

Obviously, if a person mentally regards ‘X’ and ‘not X’ as commensurate, he will not understand why they cannot both be affirmed or both be denied at once; the second and third laws of thought will seem to him prejudicial and conventional. To return to a rational viewpoint, that person has to become conscious of the radical intent of the act of negation; it leaves no space for mixtures or for additional concoctions.

Figure 3. Visualizations of negation

Bipolar logic is not a mere “convention”, for the simple reason that making a convention presupposes we have a choice of two or more alternatives, whereas bipolarity is the only way rational thought can at all proceed. We do not arbitrarily agree bipolarity, because it is inherent in the very asking of the question. To claim something to be conventional is already to acknowledge the conflict between it and the negation of it, and the lack of anything intelligible in between the two.

The motive behind the attempts of some thinkers to deny the laws of thought (i.e. the laws of proper affirmation and denial) is simply an ego ambition to “beat the system”, or more specifically (in the case of Western philosophers) to surpass Aristotle (the one who first made these laws explicit objects of study). “You say X? I will ‘up the ante’ and say Not X (etc.) – and thus show I am the greatest!”

This is not mere perversity – but a sort of natural denial instinct gone mad. For, funnily enough, to deny some suggestion (including the suggestion there are three laws of thought) is in the very nature of conceptual knowing, a protective mechanism to make sure all alternative interpretations of fact are taken into consideration. This is precisely the faculty of negation – the very one which gives rise to the need for the laws of thought! The problem here is that it is being turned on itself – it is being over-applied, applied in an absurd way.

This can go on and on ad infinitum. Suppose I say “A” (meaning “A but not notA”), you answer “not A” (meaning “notA but not A”)[4]; I reply “both A and notA”, you oppose “neither A nor notA”; what have we said or achieved? Perhaps I will now say: “all of these four alternatives”; and you will reply: “none of these four alternatives”. Then I trump you, asserting: “both these last two alternatives” and you answer: “neither of them”. And so forth. Whither and what for?

A more complex version of the same game of one-upmanship can be played with reference to the laws of thought:

- A is A (affirming the law of identity).

- A is not A (denying the law of identity).

- Both (1) and (2). A is A, and A is not A. (disregarding the law of non-contradiction).

- Neither (1) nor (2). A is not A, and A is not not A (disregarding the law of the excluded middle).

- Both (3) and (4).

- Neither (3) nor (4).

- Both (5) and (6).

- Neither (5) nor (6).

- And so on and so forth.

Thus for the first law of thought; and similarly for the other two. We do not merely have a choice of four alternatives (the first four in the above list), a so-called ‘tetralemma’, but an infinite choice of denials of denials of denials… How would we even evaluate the meaning of all these alternatives without using the laws of thought? They would all be meaningless, because every proposed interpretation would be in turn deniable.

Thus, the attempt to propose a radically “alternative logic”, instead of the standard (Aristotelian) logic, is really the end of all intelligible logic, the dissolution of all rationality. It is not a meaningful option but a useless manipulation of meaningless symbols. None of it makes any sense; it is just piling up words to give an optical illusion of depth. People who engage in such moronic games should clearly not be granted the status of “logicians”.

2. In Buddhist discourse

Opposition by some Western logicians to (one or more of) the laws of thought is mostly naïve symbolic games, without any profound epistemological or ontological reflection; of quite another caliber is the opposition to these laws found in some Buddhist literature[5]. But we can, with a bit of effort of reflection, explain away the apparent antinomies in their discourse.

When Buddhist philosophers make statements of the form “not X and not notX”, they should not (or not always) be viewed as engaging in antinomy, or in rejection of the laws of thought. Rather, such statements are abridged expressions intending: “don’t look for X and don’t look for not X”, or “don’t think X and don’t think not X”, or “don’t say X and don’t say not X”, or “don’t attach to X and don’t attach to not X”, or the like.[6]

When thus clarified, statements superficially of the form “neither X nor not X” (or similarly, in some cases, “both X and not X”) are seen to be quite in accord with logic. For the laws of thought do not deny that you cannot look for ‘X’ and for ‘not X’, or for that matter for ‘both X and not X’, or even ‘neither X nor not X’. Similarly, with regard to thinking this or that, or to claiming this or that, or to attaching to this or that, etc.

The laws of logic would only say that you cannot at once ‘look for X’ and ‘not look for X’, and so forth. It does not say you cannot at once ‘look for X’ and ‘look for not X’, and so forth. The latter situation merely asserts that the issue of X or not X ought to be left problematic. An unsolved problem is not an antinomy. The most we can say is that whereas Buddhism might be deemed to enjoin us to accept such uncertainty as final, Western logic would recommend pressing on to find a solution of sorts.

Thus, in some cases, the apparent contradictions and inclusions of middle terms in Buddhist philosophy (and similarly in some other texts) are merely verbal. They are due to inaccuracy in verbal expression, omitting significant implicit aspects of what is really meant. The reason for such verbal brevity is that the focus of such statements is heuristic, rather than existential. They are merely meant as “skillful means” (to the end of Realization), not as factual descriptions. That is to say, they are statements telling the subject how to proceed (cognitively, volitionally or in valuation), rather than telling him/her how things are.

To give an actual example from Buddhist literature, I quote the following passage from the Wake-up Sermon attributed to Bodhidharma:

“Mortals keep creating the mind, claiming it exists. And arhats keep negating the mind, claiming it doesn’t exist. But bodhisattvas and buddhas neither create nor negate the mind. This is what’s meant by the mind that neither exists nor doesn’t exist… called the Middle Way.”[7]

When we face an unresolved contradiction or an unsolved problem of any sort, we are from the point of view of knowledge in front of a void. This ‘emptiness’ can be looked upon with anxiety, as a precipice, as a deficiency of means to deal with the challenges of life. Or it may be viewed as something pregnant with meaning, a welcome opportunity to dive fearlessly into infinity. The former attitude gives rise to Western science, the latter to Zen meditation.

Or again, consider the following quotation from Huang Po’s teaching:

“If only you will avoid concepts of existence and non-existence in regard to absolutely everything, you will then perceive the Dharma.” (P. 43.)

Here again, the meaning is clear. The Zen master is not here denying existence or non-existence or both; he is just telling us not to engage in judgments like ‘this exists’ or ‘this does not exist’ that are inherent to all conceptualization. He refers to such judgments as “dualism”, because they require a decision between two alternatives. Clearly, Huang Po’s statement is not a formally contradictory ontological proposition, but a prima facie coherent epistemological injunction not to be concerned with judging whether what one experiences is real or unreal.

Admittedly, some Buddhists[8] do take such a statement as implying that existence does not exist, or that it both exists and does not exists, or neither exists nor does not exist. But as far as commonsense logic is concerned, existence does exist – i.e. whatever is, is (Aristotle’s law of identity). Any clear denial of this fundamental truth would just be self-contradictory – it would deliberately ignore the fact and implications of its own utterance (i.e. that a statement has been made, alleging a truth, by someone to someone, etc.)

More precisely, in the present context, we must acknowledge that whatever but appears, certainly exists – whether it is eventually judged to be real or illusory. On this basis, we can reasonably interpret Huang Po (at least in the citation above) as simply saying “do not ask whether some particular (or general) thing exists or not, or whether it is real or not, because such questioning diverts your attention from a much more important insight into the nature of being”.

It should be added that, even though I above admit that Huang Po’s position is prima facie coherent, it is not so coherent upon further scrutiny. He cannot strictly speaking utter a statement without using concepts and he cannot be understood by us without use of our conceptual faculty. All discourse is conceptual, even anti-conceptual discourse. That is, in the very act of preaching abstinence from concepts, he is in fact not practicing what he preaches.

This shows that even persons presumed to be enlightened need concepts to communicate, and also that such conceptuality does not apparently (judging by the claims of those who practice it) affect their being enlightened. So concepts cannot be intrinsically harmful to enlightenment, and the claim that they must be eschewed is internally inconsistent! This is not a game of words (as some might argue) – it is a logical insight that cannot be waved off. One can only at best argue against excessive conceptualization.

In any event, it must be understood that Buddhist anti-conceptual philosophy is aimed at psychological development: it is primarily a “way” or “path”. Its focus is how to react to ordinary experiences, so as to get to see the ultimate reality beyond them. It refers to the object (X or not X), not independently (as in most Western logic), but as an object of the Subject (i.e. sought out, thought of, claimed, or attached to by the subject-agent). The latter ‘subjectivity’ (i.e. dependence on the subject-agent) is very often left implicit, simply because it is so pervasive. Notwithstanding, there are contexts in which the intent is more ‘objective’ than that[9].

It should also be noticed that many of the contradictions or paradoxes that Buddhist philosophers produce in their discourse are due to their tendency to make apparently general statements that in the last analysis turn out to be less than all-inclusive. Even while believing that there is more to the world as a whole than what is commonly evident, they formulate their ideas about the phenomenal world as unqualified universal propositions. There are many examples of this tendency.

“All is unreal”, says the Dhammapada (v. 279). Calling all unreal or illusory is of course possible in imagination, i.e. verbally – by taking the predicate ‘unreal’ or ‘illusory’ from its original legitimate subjects of application and applying it to ‘all’ subjects. Implicit in this manipulation is an analogy – i.e. a statement that just as within the realm of appearance some items are found not real and labeled illusory, so we can project a larger realm in which the whole current realm of appearance would seem unreal.

This explains how people assimilate that oft-repeated Buddhist statement, i.e. why it seems thinkable and potentially plausible. But it does not constitute logical justification for it. The only possible justification would be to personally experience a realm beyond that of ordinary experience. Even then, the logically consistent way to make the statement would be “all ordinary experience is unreal” (because saying just “all” would of course logically have to include the extraordinary experience).

Another frequently found example is “existence is suffering[10].” This statement is true, all too true, about the world we commonly experience, i.e. the world of material and mental phenomena. If one is observant, one discerns that we are always feeling some unpleasantness in the background of our existence. No earthly happiness is ever complete, if only because it is tenuous. Even sexual pleasure or orgasm – which more and more of my contemporaries seem to regard as the ultimate ecstasy and goal of existence – is a pain of sorts[11].

Buddhism has displayed extreme wisdom in emphasizing the fact of suffering, because once we realize it we are by this very simple realization already well on the way to being freed of suffering. If one were visiting hell, one would not expect to experience heaven there; likewise, it is natural in this halfway world to experience some suffering. I used to suffer a lot at the sight of people getting away with injustices or other ugly acts; but lately I just tell myself: “well, I am in samsara and this is normal behavior in samsara[12] – so long as I am here, I have to expect this kind of unpleasant experience and take it in stride!”

But the statement “existence is suffering” is wrongly formulated from the logical point of view, and for that reason it is bound to lead to paradoxes. For if we believe (as Buddhists do) that suffering can eventually be overcome (specifically, when nirvana is attained), then the truth of suffering must be formulated less universally as: “mundane existence is suffering”. The usual formulation of the first Noble Truth, “existence is suffering,” is not intended to be as all-inclusive as it seems – for suffering disappears according to the third Noble Truth when we become enlightened. Therefore, to make the former consistent with the latter, it has to be rephrased more restrictively.

Another example of the tendency to artificially refuse to count the experience of enlightenment as part of the world as a whole is the idea that enlightenment takes us “beyond good and evil”. This is logically incorrect – if we regard enlightenment as the summum bonum, the ultimate good (which we do, if we enjoin people to prefer it to all other pursuits).

The phrase “beyond good and bad” is intended to stress the practical problem that pursuing good is as much a form of attachment as avoiding evil. The pursuit of worldly good things is ultimately bad, because it just ties us to this world and subjects us to the bad in it. And indeed, even the pursuit of liberation from this world, i.e. of an otherworldly good, is problematic, in that it involves the wrong attitude, a grasping or clinging attitude that is not conducive to success. All this is true, but tends towards paradox.

To avoid confusion, we must simply rephrase our goal as “beyond pursuit of good and avoidance of evil”. That is to say, we must admit that nirvana is ‘good’ in the most accurate sense of the term, while what we call ‘good’ in the world of samsara (i.e. wealth position, power, sensual pleasure, etc.) is really not much better than what we call ‘bad’. Alternatively, we should distinguish good in an absolute sense (the good of nirvana) and good in a relative sense (the goods within samsara). Relative goods would then to be classified as not so good from the absolute point of view.

The result of this change of perspective is that, rather than view existence as fundamentally bad (due to suffering), we may now view it as fundamentally good (since nirvana underlies all samsaric existence). Our common view and manner of existence is just an error of sorts, causing us much suffering; if we but return to correct cognition and behavior, we will experience the natural good at the core of all things. Here, the illusory good and evil of the mundane are irrelevant, and we are fully immersed in the real good.[13]

To conclude – Buddhist discourse often leads to paradox or contradiction because it insists on using terms in conventional ways and uttering generalities that apply to only part of the totality of experience (namely, the mundane part, to the exclusion of the supramundane part). To avoid the doctrinal problems such discursive practices cause, we must either clearly specify the terms used as having such and such conventional senses, or particularize statements that were formulated too generally (i.e. which did not explicitly take into consideration the data of enlightenment).

3. Calling what is not a spade a spade

Buddhism, no doubt since its inception, has a mix of logic and illogic in its discourse. Looking at its four main philosophical schools, Abhidharma, Prajnaparamita, Madhyamika and Yogacara, the most prone to discard the three laws of thought (i.e. Identity, Non-contradiction, Exclusion of the middle) was Madhyamika[14]. But this trend was started in the earlier Prajnaparamita, as examples from the Diamond Sutra[15] show.

We do, in this sutra, find samples of valid logical argument. For example, there is a well formed a fortiori argument in Section 12[16]: “wherever this sutra or even four lines of it are preached, that place will be respected by all beings… How much more [worthy of respect] the person who can memorize and recite this sutra…!” But we do also find plain antinomies, like “the Dharma… is neither graspable nor elusive” (said even though not graspable means elusive, and not elusive means graspable).

But the Diamond Sutra repeatedly uses a form of argument that, as a logician, I would class as a further twist in the panoply of Buddhist illogic. This states: “What is called X is not in fact X; therefore, it is called X” (or sometimes: “What is called X is truly not X; such is merely a name, which is why it is called X”).

There are over twenty samples of this argument in the said sutra. Here is one: “What the Tathagata has called the Prajnaparamita, the highest, transcendental wisdom, is not, in fact, the Prajnaparamita and therefore it is called Prajnaparamita.” Here is another: “… what are called beings are truly no beings. Such is merely a name. That is why the Tathagata has spoken of them as beings.”[17]

What I am questioning or contesting here regarding this sort of discourse is only the “therefore” or “which is why” conjunction[18]. I am not denying that one might call something by an inappropriate name, or even that words can never more than approximate what one really wants to say. But to say that one is naming something X because it is not X – this is surely absurd and untenable.

This is not merely ‘not calling a spade a spade’ – it is calling something a spade even while believing it not to be a spade! This is, at least on the surface, contrary to logic. If the label is not applicable, why apply it? Moreover, why boast about this unconscionable inversion, saying “therefore”?

To say that something “is not in fact or truly X” is to imply that the word X has a sense that the thing under consideration does not fit into; in such case, why call that very thing ‘X’ against all logic? Why not just call it ‘not X’ (or coin for it some other, more specific name) and avoid paradox!

Discourse like “such is merely a name” is self-defeating anyway, since in fact it uses names that do convey some meaning. The sentence suggests no words have any valid reference, yet relies on the effectiveness of the words it utilizes to communicate its various intentions. It is a statement that tries to exempt itself from the criticisms it levels at all statements as such.

In the examples given above, the argument depends on our understanding of words like ‘Prajnaparamita’ (i.e. perfection of wisdom) or ‘beings’ – and yet at the same time tries to invalidate any such understanding. It cannot therefore be said to communicate anything intelligible.

Without doubt, we cannot adequately express ultimate reality (or God) in words. But it remains true that we can verbally express the fact of ineffability (as just done in the preceding sentence). There is no need to devalue words as such to admit that they have their limits.

Moreover, it is very doubtful that such paradoxical statements (like “name this X because it is not X”) are psychologically expedient to attain enlightenment; they just cognitively confuse and incapacitate the rational mind. Rather than silence the inquiring mind, all they actually do is excite it with subconsciously unanswered questions. Such nonsensical statements are products of an unfortunate fashion that developed in Buddhism at a certain epoch[19].

That sort of intellectual perversity came to seem profound, as it does to some postmodern thinkers in the West today, precisely because a logical antinomy implies nothing – and that emptiness of meaning is (wrongly) equated with the Emptiness underlying all phenomena. The gaping hole in knowledge left by antinomy gives the illusion of being pregnant with meaning, whereas in fact it is just evidence of ignorance. Note this well.

It should be added that there is indeed a sort of structural paradox in the meditative act – but the Diamond Sutra’s habit of ‘calling not a spade a spade’ is not it. The paradox involved is that if we pursue enlightenment through meditation, we cannot hope to attain it, for then our ego (grasping at this transcendental value as at a worldly object) is sustained; yet, meditation is the best way to enlightenment. So we must ‘just do it’ – just sit and let our native enlightenment (our ‘Buddha nature’) shine forth eventually.

It should also be reminded that Buddhism is originally motivated by strong realism. It is essentially a striving towards Reality. In this perspective, the Buddhist notion of “suchness” may be considered as a commitment to the Law of Identity. The enlightened man is one who perceives things, in particular and in general, such as they really are.

This is brought out, for instance, in the following Zen exchange. A monk asked Li-shan: “What is the reason [of Bodhidharma’s coming from the West, i.e. from India to China]”, to which the Zen master replied “Just because things are such as they are”, and in D. T. Suzuki’s commentary that this refers to “Suchness”[20].

Addendum (2010), concerning the Diamond Sutra’s discourse. Although its form is paradoxical, it seems intelligible. How is this to be explained? What is the underlying logic that makes people accept such discourse in spite of its formal flaws? I can answer this with reference to another instance of such discourse, inspired by the said sutra. In The Zen Teaching of Huang Po (pp. 64-65), we find the following discourse, as translated by John Blofeld: “The fundamental doctrine of the Dharma is that there are no dharmas, yet that this doctrine of no-dharma is in itself a dharma; and now that the no-dharma doctrine has been transmitted, how can the doctrine of the dharma be a dharma?” (Blofeld explains that he introduced the word ‘doctrine’ in place of ‘dharma’ to avoid the confusion of the original Chinese sentence.)

Why is this statement somewhat intelligible? Let me rephrase it a little (square brackets mine): “The fundamental doctrine of the Dharma is that there are no [verbal] dharmas, yet that this doctrine of no-dharma is in itself a dharma; and now that the no-dharma doctrine has been transmitted [wordlessly], how can the doctrine of the dharma be a [verbal] dharma?” In other words, the non-verbal dharma transmission cannot be replaced by a verbal transmission, such as the present words. Such words can merely talk about or somewhat describe the actual dharma transmission, but are incapable of being a substitute for it. Dharma transmission remains possible only non-verbally. As can be seen, the paradox arises only due to incompetent verbalization (if not a predilection for paradoxical statements). The underlying idea (that transmission of the mind of Zen can only be effectively performed wordlessly) is not paradoxical. It is quite intelligible (certainly there is no natural necessity that a mere description can do the job) and it can even be verbalized without paradox (as here done).

Drawn from Logical and Spiritual Reflections (2008-9), book 3, chapters 8-10 and addendum 1.

[1] Incidentally, I notice people on the Internet nowadays labeling the three laws of thought (LOT): LOI, LNC and LEM, for brevity’s sake. Sure, why not?

[2] Some logicians accept the law of non-contradiction as unavoidable, but consider the law of the excluded middle as expendable: this modern notion is quite foolish. Both laws are needed and appealed to in both deductive logic and in inductive logic. They do not only serve for validation (e.g. of syllogisms or of factorial inductions), but they generate questions and research (e.g. what does this imply? or what causative relation can be induced from that?). Moreover, they are mirror images of each other, meant to complement each other so as to exhaust all possibilities, and they ultimately imply each other, and both imply and are implied by the law of identity.

[3] Note that difference does not imply incompatibility. Two things, say X and Y, may be different, yet compatible – or even imply each other. We are well able to distinguish two things (or characteristics of some thing(s)), even if they always occur in tandem and are never found elsewhere. Their invariable co-incidence does not prevent their having some empirical or intellectual difference that allows and incites us to name them differently, and say that X is not the same thing as Y. In such case, X as such will exclude Y, and not X as such will include Y, even though we can say that X implies Y, and not X implies not Y.

[4] Note that if we start admitting the logical possibility of “A and notA” (or of “not A and not notA”), then we can no longer mention “A” (or “notA”) alone, for then it is not clear whether we mean “A with notA” or “A without notA” (etc.). This just goes to show that normally, when we think “A” we mean “as against notA” – we do not consider contradictory terms as compatible.

[5] I am of course over-generalizing a bit here, for emphasis. There are of course savvier Western logicians and less savvy Oriental (including Buddhist) logicians. A case of the latter I have treated in some detail in past works is Nagarjuna.

[6] For example, the following is a recommendation to avoid making claims of truth or falsehood: “Neither affirm nor deny… and you are as good as enlightened already.” Sutra of Supreme Wisdom, v. 30 – in Jean Eracle (my translation from French).

[7] P. 53. This passage is particularly clear in its explanation of “neither exists nor does not” as more precisely “is neither created nor negated”. Whereas the former is logically contradictory, the latter is in fact not so. What is advocated here is, simply put, non-interference.

[8] In truth, Huang Po is among them, since elsewhere he piously states: “from first to last not even the smallest grain of anything perceptible has ever existed or ever will exist” (p. 127). This is a denial of all appearance, even as such. Of course, such a position is untenable, for the existence of mere appearance is logically undeniable – else, what is he discussing? Before one can at all deny anything, one must be able to affirm something. Also, the act of denial is itself an existent.

[9] For a start, to claim a means as skillful is a kind of factual description.

[10] This is the usual translation of the Sanskrit term is dukkha. This connotes not only physical and emotional pain, but more broadly mental deficiencies and disturbances, lack of full satisfaction and contentment, unhappiness, absence of perfect peace of mind.

[11] If we are sufficiently attentive, we notice the pain involved in sexual feelings. Not just a pain due to frustration, but a component of physical pain in the very midst of the apparent pleasure.

[12] Or, using Jewish terminology: “I am in galut (exile, in Hebrew), and such unpleasantness is to be expected here”. Note in passing, the close analogy between the Buddhist concept of samsara and the kabbala concept of galut.

[13] We could read S. Suzuki as saying much the same thing, when he says: “Because we are not good right now, we want to be better, but when we attain the transcendental mind, we go beyond things as they are and as they should be. In the emptiness of our original mind they are one, and there we find perfect composure” (p.130).

[14] See my work Buddhist Illogic on this topic, as well as comments on Nagarjuna’s discourse in my Ruminations, Part I, chapter 5. I must stress that my concern, throughout those previous and the present critiques, is not to reject Buddhism as such, but to show that it can be harmonized with reason. I consider quite unnecessary and counterproductive, the attitude of many Buddhist philosophers, who seemingly consider Realization (i.e. enlightenment, liberation, wisdom) impossible without rejection of logic. My guiding principle throughout is that they are quite compatible, and indeed that reason is an essential means (together with morality and meditation) to that desirable end.

[15] Judging by its Sanskrit language, the centrality of the bodhisattva ideal and other emphases in it, this sutra is a Mahayana text. It is thought to have been composed and written in India about 350 C.E., though at least one authority suggests a date perhaps as early as 150 C.E. For comparison, Nagarjuna, the founder of Madhyamika philosophy, was active circa 150-200 C.E.; thus this Prajnaparamita text was written during about the same period, if not much later.

[16] Mu Soeng, p. 111.

[17] In Mu Soeng: pp. 145 and 151, respectively. I spotted a similar argument in another Mahayana text: “And it is because for them [the bodhisattvas] training consists in not-training that they are said to be training” (my translation from a French translation) – found in chapter 2, v. 33 of the “Sutra of the words of the Buddha on the Supreme Wisdom” (see Eracle, p. 61).

[18] Assuming the translation in this edition is correct, of course (and it seems quite respectable; see p. ix of the Preface). My point is that no logician has ever formally validated such an argument; and in fact it is formally invalid, since the conclusion effectively contradicts a premise.

[19] Although not entirely absent in the earlier Abhidharma literature and the later Yogacara literature, they are not uncommon in some Prajnaparamita literature (including the Diamond Sutra) and rather common in Madhyamika literature.

[20] The Zen Doctrine of No-mind, p. 93.