1. Fallacious criticisms of selfhood

Since writing Buddhist Illogic, I have been reviewing Buddhist arguments against selfhood more carefully, and I must say that – while they continue to inspire deeper awareness of philosophical issues in me – I increasingly find them unconvincing, especially with regard to logical standards.

Buddhists conceive of the self as a non-entity, an illusion produced by a set of surrounding circumstances (‘causes and conditions’), like a hole in the middle of a framework (of matter or mind or whatever). But I have so far come across no convincing detailed formulation of this curious (but interesting) thesis, no clear statement that would explain how a vacuity can seemingly have consciousness, will and values. Until such a theory is presented, I continue to accept self as an entity (call it soul) of some substance (spirit, say). Such a self is apparently individual, but might well at a deeper level turn out to be universal. The individuation of soul might be an illusion due to narrow vision, just as the individuation of material bodies seems to be.

Criticisms of the idea of self are no substitute for a positive statement. It is admittedly hard to publicly (versus introspectively) and indubitably demonstrate the existence of a soul, with personal powers of cognition, volition and affection. But this theory remains the most credible, in that the abstract categories it uses (entity, substance, property, causality) are already familiar and functional in other contexts. In contrast, the impersonal thesis remains mysterious, however open-minded we try to be. It may be useful for meditation purposes, but as a philosophical proposition it seems wanting.

Generally speaking, I observe that those who attempt to rationalize the Buddhist no-self thesis indulge in too-vague formulations, unjustified generalizations and other non-sequiturs. A case in point is the work Lotus in a Stream by Hsing Yun[1], which I have recently reread. The quotations given below as examples are from this work.

“Not only are all things impermanent, but they are also all devoid of self-nature. Having no self-nature means that all things depend on other things for their existence. Not one of them is independent and able to exist without other things” (pp. 86-87).

Here, the imprecision of the term “existence” or “to exist” allows for misrepresentation. Western thought would readily admit that all (or perhaps most) things come to be and continue to be and cease to be and continue to not-be as a result of the arrival, presence, departure or absence of a variety of other things. But that is very different from saying that their being itself is dependent: for us, facts are facts, i.e. once a thing is a past or present fact, nothing can change that fact, it is not “dependent” on anything. Yet, I contend, Buddhists seem to be trying to deny this, and cause confusion by blurring the distinction between change over different time and place, and change within identical time and place.

“The meaning of the word ‘things’ in these statements is all phenomena, both formed and formless, all events, all mental acts, all laws, and anything else you can think of.”

Here, the suggestion is that impermanence concerns not only phenomena, which strictly speaking are material or mental objects of perception, but also abstract objects. The terms “formless” and “laws” and “anything you can think of” suggest this. But of course such a statement surreptitiously slips in something we would not readily grant, though we would easily admit that phenomena are impermanent. The whole point of a “law” is that it is a constant in the midst of change, something we conceive through our rational faculty as the common character of a multitude of changing phenomenal events. The principle of Impermanence is not supposed to apply to abstracts. Indeed, it is itself an abstract, considered not to be impermanent!

“To say that nothing has a self-nature is to say that nothing has any attribute that endures over long periods of time. There is no ‘nature’ that always stays the same in anything anywhere. If the ‘nature’ of a thing cannot possibly stay the same, then how can it really be a nature? Eventually everything changes and therefore nothing can be said to have a ‘nature,’ much less a self-nature.”

Here, the author obscures the issue of how long a period of time is – or can be – involved. Even admitting that phenomena cannot possibly endure forever, it does not follow that they do not endure at all. Who then is to say that an attribute cannot last as long as the thing it is an attribute of lasts? They are both phenomena, therefore they are both impermanent – but nothing precludes them from enduring for the same amount of time. The empirical truth is: some attributes come and/or go within the life of a phenomenal thing, and some are equally extended in time. Also, rates of change vary; they are not all the same. The author is evidently trying to impose a vision of things that will comfort his extreme thesis.

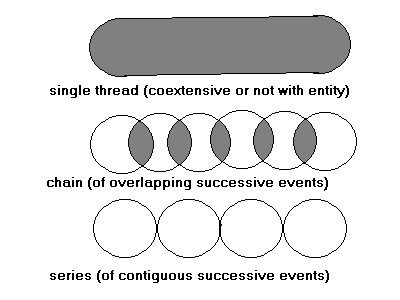

We can, incidentally, conceive of different sorts of continuity of conjunctions of phenomena (see diagram below). An essential attribute of a thing would coexist fully, like an underlying thread of equal time length. A weaker scenario of continuity would be a chaining of different events, such that the first shares some time with the second, which shares some with the third, and so forth, without the first and third, second and fourth and so on having time in common. In some cases, continuity may be completely illusory, in that events succeed each other contiguously in time without sharing any time.

Figure 1. Three types of continuity

Hsing Yun goes on arguing:

“the body… is a delusion caused by a brief congregation of the physical and mental components of existence Just as a house is made of many parts that create an appearance, so the body… When those parts are separated, no self-nature will be found anywhere.”

That a house or human body is an aggregate of many separable elements, does not prove that when these elements are together (in a certain appropriate way, of course) they do not collectively produce something new. The whole may be more than its constituent parts, because the whole is not just the sum of the parts but an effect of theirs. The bricks of a house do not just add up to a house, but together become a house when placed side by side in certain ways; if placed apart (or together in the wrong way) they do not constitute a house (but at best a pile of bricks). Similarly for the atoms forming a molecule, the molecules forming a living cell, the cells causing a human organism. At each level, there is a causal interplay of parts, which produces something new that is more than the parts, something we call the whole, with its own distinct attributes and properties.

It is thus quite legitimate to suppose that when matter comes together in a certain way we call a live human body, it produces a new thing called the self or soul or spirit, which thing we regard as the essence of being human because we attribute to it the powers of consciousness and volition that we evidently display (and which the constituent matter in us does not, as far as we can see, separately display). That this idea of self is a hypothesis may be readily admitted; but to anyone conscious of the inductive basis of most human knowledge that does not constitute a criticism (all science develops through hypotheses). The important point to note is that Buddhist commentators like this one give arguments that do not succeed in proving what they purport to prove.

Here are some more examples, relating to the notion of “emptiness”:

“Dependent origination means that everything is produced from conditions and that nothing has an independent existence of its own. Everything is connected to everything else and everything is conditioned by everything else. ‘Emptiness’ is the word used to describe the fact that nothing has an independent nature of its own” (p. 94).

Here, the reader should notice the vagueness of terms like “connection” or “conditioning”. They are here used without nuance, without remark that very many kinds and degrees of causal relation may be involved. The impression made on the reader is that everything is equally bound to everything else, however far or near in space and time. But that is not merely untrue – it is conceptually untenable! Concepts of causality arise with reference to a specific relation, which some things have with each other and some things lack with each other. If all things had the same causal relation to all other things, no concept of a causal relation would arise nor be needed. We can very loosely say that the cause of a cause of a thing is “causally related” to it, but causal logic teaches us that the cause of a cause of a thing is not always itself “a cause” of it in the strict sense. And even if it is, it may not be so in the same degree. It follows that Hsing Yun is here again misleading us.

“Emptiness does not mean nothingness… all things have being because they all do exist interdependently” (p.97).

Here, the image communicated to us is that each thing, although in itself empty of substance, acquires existence through its infinity of relations (dependencies) to all other things, each of which is itself empty of substance. We must ask, is this theoretical scenario credible? Does an infinity of zeros add up to a non-zero? What are those “relations” between “things”? Are they not also “things”? Are they not also empty, in which case what gives them existence? The concept of relation implies the pre-existence of things being related (terms); if all that exists are relations, is the concept still meaningful?

Furthermore, what does interdependence (a.k.a. co-dependence) mean, exactly? Is an embrace in mid-air between two or more people equivalent to a mutual support? If I cannot support myself, can I support you? The notion is unconscionable.

“Nothing is unchangeable or unchanging. All phenomena exist in succession. They are always changing, being born, and dying.”

Here, the author has simply dropped out the (previously acknowledged) and very relevant fact of enduring. To convince us that the world is nothing but flux, he mentions birth, change and death – but eclipses the fact of living, if only for a little while! The phrase “they are always” does not necessarily mean “each of them in every moment.”

“A cause (seed) becomes an effect (fruit), which itself contains the cause (seed) for another effect, and so on. The entire phenomenal world works just like this” (p. 98).

Here, we are hastily dragged into a doubtful generalization. The description of the cycle of life, with procreation from generation to generation, does not necessarily fit other causal successions. Causation in the world of inanimate matter obeys its own laws, like Newton’s Laws of Motion for example. There is nothing truly equivalent to reproduction in it, to my memory. To convince us, the author would have to be much more precise in his analogies. Philosophers have no literary license.

“If we were to break a body down into its constituent parts, the body would no longer exist as a body.”

So what? Is that meant to explain or prove “emptiness”? If you kill an animal and cut it up, of course you will not find the life in it, or the consciousness it had, or its “animal nature”. It does not follow that when the animal is alive and well, it lacks these things!

“The meanings of the words ‘above’ and ‘below’ depend on where we are. They do not have absolute meanings. It is like this with all words and all relationships between things” (p. 99).

Again, a hasty generalization – from specifically relative terms to all words. Every grammarian knows that relative terms are just one type of term among others. That the former exist does not imply that the latter have the same character or properties. Similarly, Hsing Yun argues that the relativity of a word like “brightness” (our characterization of the brightness of a light is subjective and variable) exemplifies the relativity of all terms. But here again, he is passing from an obvious case to all cases, although many qualifications are based on stricter, scientific measurement. Moreover, describing how a piece of cloth may have various uses, as a shirt or as a skirt, he argues:

“It is the same piece of cloth in all cases, but since it is used differently, we have different names for it. All words are like this; their meanings depend on how and where they are used.”

This is supposed to convince us that words are “false and wavering” and help us to better understand emptiness. But the truthfulness and accuracy of language are clearly not at stake here, so the implied negative conclusion is unwarranted. The proof is that we all understand precisely his description of the changing practical role of the piece of cloth. “Cloth can be used as shirt or as skirt” is a perfectly legitimate sentence involving the natural modality “can” and two predicates in disjunction for a single subject (A can be B or C). Of course, if one starts with the idea that language can only consist of sentences with two terms and one modality (A is B), then one will be confused by more complex situations. But if one’s understanding of human thought is more developed, one does not fall into foolish conclusions.

Lastly, Hsing Yun refers to “the relative natures of our perceptions” to justify the idea of emptiness. He describes two people watching a snowfall, one is a poet sitting in his warm house, the other a homeless man shivering outdoors. The first hopes the snow will continue to fall, so he can enjoy watching it; the second fears that if the snow continues to fall, he may freeze to death. The author concludes:

“Both are seeing the same scenery, but since their conditions are different they perceive it very differently.”

Thus, perceptions are “false” and emptiness “underlies” them. Here again, his interpretation of the situation is tendentious, designed to buttress his preconceived doctrines. To be precise, the two people correctly perceive the (more or less) same snowy scene; what differs is their evaluation of the biological consequences of what they are perceiving (or more precisely still, what they anticipate to further experience). There is no relativity of perception involved! We have two quite legitimate sentences, which are both probably true “I’ll enjoy further snow” and “I’ll be killed by further snow”. “I” being the poet in one case and the poor man in the other case, there is no contradiction between them.

By arguments like those we have analyzed, Hsing Yun arrives at the overall conclusion that:

“The universe can only exist because all phenomena are empty. If phenomena were not empty, nothing could change or come into being. Being and emptiness are two sides of the same thing” (p. 100).

But none of his premises or arguments permits us to infer or explicate such conclusion. It is a truism that if your cup is full, you cannot add to it; or if you have no room to move into, you cannot move. But this is not what the author is here talking about; the proposed thesis is of course much more radical, though still largely obscure. All we are offered are dogmatic statements, which repeat on and on what the Buddha is claimed to have said.

I am personally still quite willing to believe that the Buddha did say something enlightening about interdependence, impermanence, selflessness and emptiness, but the words used were apparently not very clear. I just hope that his difficulty was merely in finding the right words to express his insights, and that the reasoning behind those words was not as faulty as that I have encountered in the work of commentators so far!

Still, sentences like the following from the Flower Garland Sutra are deliciously pregnant with meaning, challenging us to keep digging[2]:

“When wind moves through emptiness, nothing really moves.”

2. What “emptiness” might be[3]

The following is an attempt to eclectically merge the Western and Indian idea of a ‘soul’ with aspects of the Buddhist idea that we are “empty” of any such substance. What might the ‘soul’ be, what its place in ‘the world’, what its ‘mechanics’? Can we interpret and clarify the notion of “emptiness” intellectually?

The Buddhist notion of “emptiness” (in its more extremist versions) is, as far as I am concerned to date, unconvincing. If anything is empty, it is the very concept of emptiness as used by them – for they never clearly define it or explain it. Philosophy cannot judge ideas that remain forever vague and Kafkaesque accusations. The onus is on the philosophers of emptiness to learn to express their ideas more verbally.

a. Imagine the soul as an entity in the manifold, of (say) spiritual substance, a very fine energy form somewhat distinct from the substances of the mental domain (that of imaginations) and of the material domain (that of physical phenomena, regarded as one’s body and the world beyond one’s body).[4]

b. While solipsism is a logically acceptable proposition, equally conceivable is the notion that the soul may be one among many in a large population of souls scattered in the sea of existence, which includes also the coarser mental and material energies. These spiritual entities may well have common natures and behavior tendencies, and be able to impact on each other and become aware of each other.

Those many souls may conceivably be expressions of one and the same single Soul, and indeed mind and matter may also be expressions of that one Soul, which might perhaps be identified with (a rather Hindu viewpoint) or be a small emanation of (a more Jewish view) what we call God. Alternatively, the many souls may be interrelated more in the way of a network.

The latter view could be earmarked as more Buddhist, if we focus on its doctrine of “interdependence.” However, we can also consider Buddhism compatible with the idea of a collective or root Soul, if we focus on its doctrine of an “original, common ground of mind.” This refers to a mental ocean, whence all thoughts splash up momentarily (as seemingly evident in meditation). At first individual and psychological, this original substance is eventually regarded as universal and metaphysical, on the basis of a positivistic argument[5] that since even material sensations are known only through mind, we can only suppose that everything is mind. Thus, not only ‘thoughts,’ but all ‘things’ are mere turbulences in this primordial magma. Even individual ‘selves’ are merely drops of this mental sea water that momentarily have the illusion of separateness and personal identity.

c. For each individual soul (as for the greater Soul as a whole), the mind, the body, and the world beyond, of more matter, mind and spirit energies, may all be just projected ‘images’ (a viewpoint close to Bishop Berkeley’s in the West or Yogachara philosophers in Buddhism). This is not an affirmation by me, I am merely trying to demystify this theory and take it into consideration, note well.

The term image, here, does not signify image of anything else. Such images are perhaps media of self-expression and discourse of the soul (or Soul). That is, the ‘world around me’ may be a language the soul creates and uses to express itself and communicate with itself (and with other eventual souls).

Granting there are objectively are many souls, we can observe that these souls have many (perhaps most) of their images in common. This raises an important question, often asked in relation to such Idealism. If our worlds (including the physical aspects) are personal imaginations, how come so much of their contents agree, and how is it that they seem to be subject to the same ‘laws of nature’?

One possible answer is to assume the many souls to be emanations of a central Soul (animal, human or Divine). In that case, it is no wonder that they share experiences and laws.

Alternatively, we could answer that like images just happen to be (or are by force of their nature and habits) repeatedly projected by the many souls. In this way, they seemingly share a world (in part, at least), even though it is an imaginary one. Having delusions in common, they have perceptions in common. They can thus interact in regular ways in a single apparent ‘natural environment,’ and develop collective knowledge, society, culture, technology, ethics, politics and history. Thus, we are not forced to assume one common, objective world. It may well be that each soul projects for itself certain images that other souls likewise project for themselves, and these projected images happen to be the same upon comparison.

d. Viewed as a ball of subtle energy, the soul can well have its own spiritual ‘mechanics’ – its outer and inner shapes and motions, the creases and stirrings within it and at the interface with the mental and material (and spiritual) energies around it, the mathematics of the waves which traverse it and its environment, like a creature floating in the midst of the sea.

Consciousness and will, here viewed as different powers of projection, are the ways the soul interacts with itself and its supposed surrounds.

These wave-motion capacities of the soul, are naturally subject to some ‘laws’ – although the individual soul has some considerable leeway, it is not free to operate just any way it pleases, but tends to remain under most circumstances in certain fixed or repeated patterns. These (spiritual, psychological) ‘laws’ are often shared with other souls; but each of them may also have distinct constraints or habits – which gives each its individuality. Such common and individual ‘laws’ are their real underlying natures, as distinct from the image of ‘nature’ they may project.

In the event that the plurality of souls is explained by a single great Soul, there is even less difficulty in understanding how they may be subject to common laws. On the other hand, the individualities of the fragmentary souls require explanation. Here, we must suppose either an intentional, voluntary relinquishment of power on the part of the great Soul (so that little souls have some ignorance and some freedom of action) or an involuntary sleep or weakness (which latter thesis is less acceptable if we identify the larger soul with God).

With regard to the great Soul as a whole, it may either be subject to limitations and forces in its consciousness and volition – or it may be independent of any such natural restrictions or determinations, totally open and free. Our concept of God opts for the latter version, of course – whence the characterizations of omniscient and omnipotent (and all-good, granting that evil is an aberration due to ignorance and impotence).

e. The motive and end result of theses like the above is ethical. They aim and serve to convince people that the individual soul can find liberation from the constraints or habits it is subject to, by realizing its unity with other individual souls. ‘Realizing’ here means transcending one’s individuality by becoming aware of, identifying oneself with and espousing the cause of, other entities of the same substance, or the collective or root Soul. Thus, enlightenment and liberation are one and the same. Ultimately, the individuals are to abandon individuation and merge with all existence, melting back into the original source.

This doctrine presupposes that the individual soul self-constructs, and constructs the world around, in the sense that it defines (and thus effectively divides) itself out from the totality. This illusion of individuation is the sum of its creativity and activity, and also its crucial error. The individual soul does not of course create the world (which is its source); but it produces the virtual world of its particular world-view, which is its own prison and the basis of all its suffering, its “samsara.”

Realizing the emptiness of self would be full awareness in practice that the limited self is an expression of the ignorance and stupidity that the limited self is locked into because of various beliefs and acts. Realizing the emptiness of other entities (material, mental and spiritual) around one, would be full awareness in practice that they are projections of the limited self, in the sense that such projection fragments a whole into parts. Ultimately, too, the soul is advised to realize that Soul, souls and their respective projections are one continuum.

Those who make the above-implied promises of enlightenment and liberation claim justification through personal meditative experiences or prophetic revelations. I have no such first-hand experience or authority, but here merely try to report and elucidate such doctrines, to check their conceivability and understand them. To me, no one making philosophical utterances can claim special privileges; all philosophers are equally required to present clear ideas and convincing arguments.

f. The way to such realization is through meditation, as well as altruistic and sane action.

In the framework of the above-mentioned Buddhist philosophy of “original ground” (also called “Buddha mind”), meditation may be viewed as an attempt to return to that profound, natural, eternal calm. Those who attain this level of awareness are said to be in “nirvana.” The illusion of (particular, individual) selfhood arises from disturbances[6], and ceases with their quieting. The doctrine that the illusory self is “empty,” means that we must not identify with any superficial flashes of material or mental excitement, but remain grounded in the Buddha mind.

For example, the Tibetan work The Summary of Philosophical Systems[7] warns against the self being either differentiated from or identified with “the psycho-physical constituents.” I interpret this statement (deliberately ignoring its paradoxical intent[8]) to mean that there is nothing more to the illusory self than these phenomenal manifestations, and therefore that they cannot be the real self. Dogmatic Buddhists provocatively[9] insist that no real self exists, but moderates do seem to admit it as equivalent to the universal, original ground.

Buddhist philosophers generally admit of perception and conception, but ignore or deny direct self-awareness. Consistently enough, they reject any claim to a soul (spiritual substance), since they consider that we have no real experience thereof. For them, the “psycho-physical constituents” are all we ordinarily experience or think about, so that soul must be “empty” (of anything but these constituents) and illusory (since these are not enough to constitute a soul). But this theory does not specify or explain the type of consciousness involved in the Buddha mind, or through which “emptiness” is known!

Another way to view things is to admit that there are three sources of knowledge, the perceptual (which gives us material and mental phenomenal manifestations), the conceptual (which gives us abstracts), and thirdly the intuitive (which gives us self-knowledge, apperception of the self and its particular cognitions, volitions and valuations). Accordingly, we ought to acknowledge in addition to material and mental substances, a spiritual substance (of which souls are made, or the ultimate Soul). The latter mode of consciousness may explain not only our everyday intuitions of self, but perhaps also the higher levels of meditation.

What we ordinarily consider our “self” is, as we have seen earlier, an impression or concept, based on perception and conception, as well as on intuitive experience. In this perspective, so long as we are too absorbed in the perceptual and conceptual fields (physical sensations, imaginations, feelings and emotions, words and thoughts, etc.), we are confused and identify with an illusory self. To make contact with our real (individual, or eventually universal) self, we must concentrate more fully on the intuitive field. With patience, if we allow the more sensational and exciting presentations to pass away, we begin to become aware of the finer, spiritual aspects of experience. That is meditation.

3. Feelings of emptiness

There is another sense of the term “emptiness” to consider, one not unrelated to the senses previously discussed. We all have some experience of emotional emptiness.

One of the most interesting and impressive contributions to psychology by Buddhism, in my view, is its emphasis on the vague enervations we commonly feel, such as discomfort, restlessness or doubt, as important motives of human action. Something seems to be wanting, missing, urging us to do something about it.

These negative emotions, which I label feelings of emptiness, are a cause or expression of samsaric states of mind. This pejorative sense of “emptiness” is not to be confused with the contrary “emptiness” identified with nirvana. However, they may be related, in that the emotions in question may be essentially a sort of vertigo upon glimpsing the void.[10]

Most people often feel this “hole” inside themselves, an unpleasant inner vacuity or hunger, and pass much of their time desperately trying to shake it off, frantically looking for palliatives. At worst, they may feel like “a non-entity”, devoid of personal identity. Different people (or a person at different times) may respond to this lack of identity, or moments of boredom, impatience, dissatisfaction or uncertainty, in different ways. (Other factors come into play, which determine just which way.)

Many look for useless distractions, calling it “killing time”; others indulge in self-destructive activities. Some get the munchies; others smoke cigarettes, drink liquor or take drugs. Some watch TV; others talk a lot and say nothing; others still, prefer shopping or shoplifting. Some get angry, and pick a quarrel with their spouse or neighbors, just to have something to do, something to rant and rave about; others get into political violence or start a war. Some get melancholic, and complain of loneliness or unhappiness; others speak of failure, depression or anxiety. Some masturbate; others have sex with everyone; others rape someone. Some start worrying about their physical health; others go to a psychiatrist. Some become sports fanatics; others get entangled in consuming psychological, philosophical, spiritual or religious pursuits. Some become workaholics; others sleep all day or try to sink into oblivion somehow. And so on.

As this partial and disorderly catalogue shows, everything we consider stupidity or sin, all the ills of our psyche and society, or most or many, could be attributed to this vague, often “subconsciously” experienced, negative emotion of emptiness and our urge to “cure” it however we can. We stir up desires, antipathies or anxieties, compulsions, obsessions or depression, in a bid to comprehend and smother this suffering of felt emptiness. We furnish our time with thoughts like: “I think I am falling in love” or “this guy really bugs me” or “what am I going to do about this or that?” or “I have to do (or not to do) so and so”. It is all indeed “much ado about nothing”.

If we generalize from many such momentary feelings, we may come to the conclusion that “life has no meaning”. That, to quote William Shakespeare:

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

Macbeth (act V, scene 5).

Of course, we can and often do also react more positively, and give our life more constructive meaning. I believe this becomes possible once we are able to recognize this internal vacuum when we feel it, and make sure we do not react to it in any of the negative ways we unconsciously tend to react. Once we understand that this feeling of emptiness cannot be overcome by such foolish means, we can begin to look for ways to enjoy life, through personal growth, healthy activities, helping others, learning, creativity, productiveness, and so forth.

Regular meditation is a good remedy. Sitting quietly for long periods daily makes it easier to become and remain aware of emotional emptiness when it appears. Putting such recurring bad feelings into perspective gradually frees us from them. They just seem fleeting, weak and irrelevant. Life then becomes a celebration of time: we profit from the little time we have in it to make something nice out of it.

Drawn from Phenomenology (2003), chapter 5:5-6 and appendix 2.

[1] See in particular chapters 7-9. (The author is a Chinese Buddhist monk, b. 1928.)

[2] For instance, is there a state of consciousness in which one experiences space-time as a static whole?

[3] This essay was initially written for the book Buddhist Illogic, but at the time I decided that it was not sufficiently exhaustive and consistent and did not belong there. I have since then improved it somewhat.

[4] Note that animists regard even plants and stones as spiritual.

[5] As I make clear elsewhere, I am not personally convinced by this extreme argument.

[6] It is not clear to me how these disturbances are supposed by this theory to arise in the beginning. But this issue is not limited to Buddhism: for philosophers in general, the question is how did the one become many; for physicists, it is what started the Big Bang; for monotheists, it is why did God suddenly decide to create the universe? A deeper question still is how did the existence arise in the first place, or in Buddhism, where did the original ground come from?

[7] See Guenther, p. 67.

[8] Having dealt with the fallacy of the tetralemma in my Buddhist Illogic.

[9] Looking at the history of Indian philosophy, one cannot but notice the one-upmanship involved in its development. The concept of samsara (which I believe was originally intended as one of totality, albeit a cyclical one) was trumped by that of nirvana (again a totality, though beyond cycles), which was then in turn surpassed by that of “neither samsara nor nirvana, nor both” (the Middle Way version). Similarly, the concept of no-self is intended to outdo that of Self.

[10] These emotions are classified as forms of “suffering” (dukkha) and “delusion” (moha). According to Buddhist commentators, instead of floating with natural confidence on the “original ground” of consciousness as it appears, a sort panic occurs giving rise to efforts to establish more concrete foundations. To achieve this end, we resort to sensory, sensual, sentimental or even sensational pursuits.